Walk the halls of the U.S. Capitol today, and you will feel it—a palpable tension that transcends mere policy disagreement. What was once a forum for vigorous debate, compromise, and eventual governance has, over decades, hardened into a theater of entrenched partisan warfare. The U.S. Congress, the first branch of government designed by the Founders to be closest to the people, is now often characterized by gridlock, brinksmanship, and a deepening ideological chasm that mirrors the division in the American public itself. This is not the normal ebb and flow of American politics. It is a fundamental restructuring of the political landscape, with profound consequences for the nation’s ability to address complex challenges.

This article will analyze the multifaceted phenomenon of partisan polarization in Congress. We will move beyond the headlines and cable news soundbites to explore the historical, structural, and social forces that have driven Democrats and Republicans into increasingly separate and hostile camps. By examining the data, understanding the mechanisms, and assessing the consequences, we can move toward a more nuanced comprehension of why Congress is so divided and what, if anything, can be done to bridge the gap.

Section 1: The Evidence of Division – Quantifying the Chasm

Before analyzing the causes, it is essential to establish the extent of the divide. Political scientists have developed robust methods to measure congressional polarization, and the data paints a stark picture.

1.1 The DW-NOMINATE Score: A Century-Long View

The gold standard for measuring congressional voting patterns is the DW-NOMINATE (Dynamic Weighted NOMINAl Three-Step Estimation) score, developed by political scientists Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal. This system analyzes every roll-call vote, plotting each member of Congress on a spatial map, typically along a single liberal-conservative dimension.

The historical trends are undeniable:

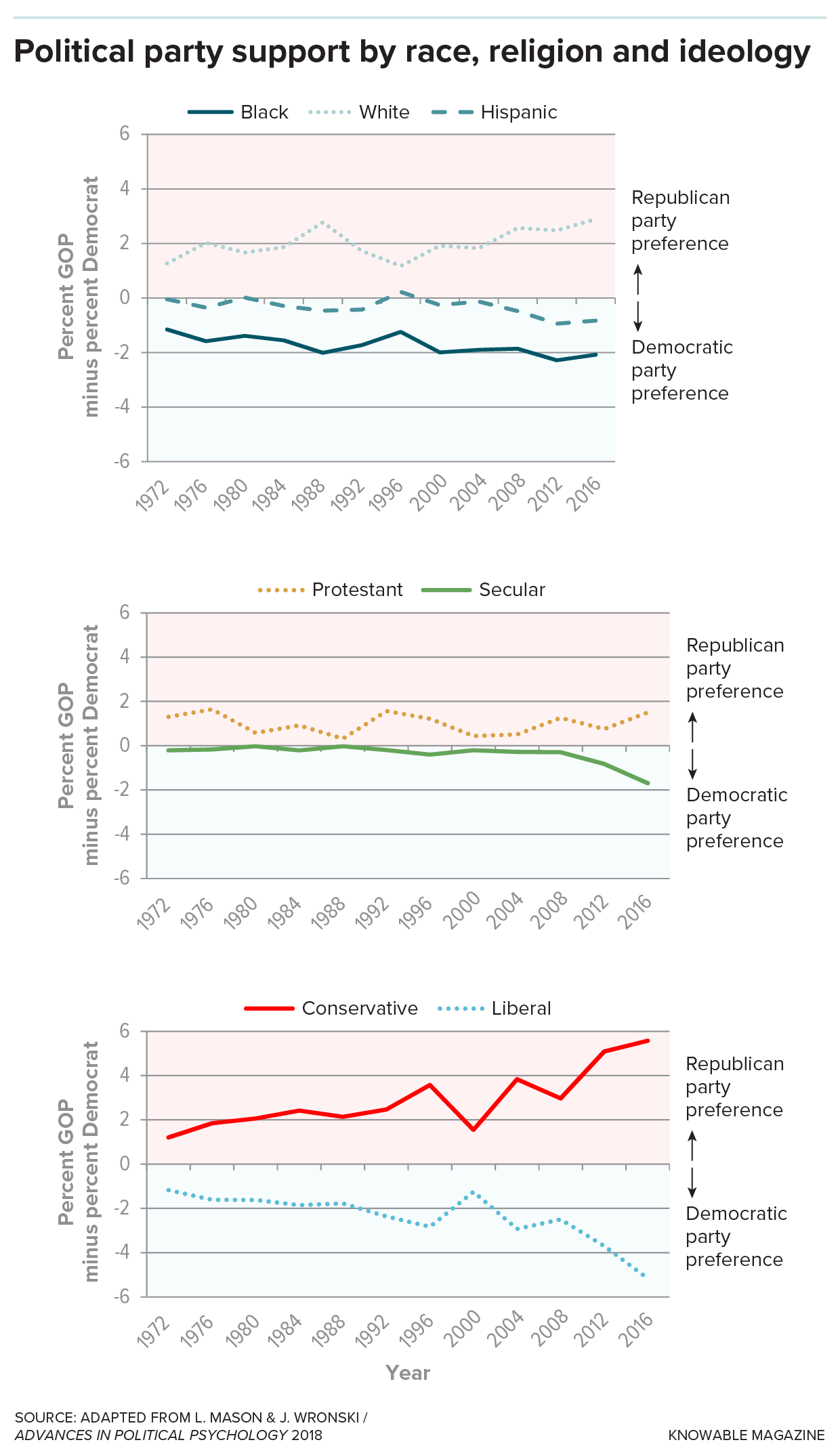

- The Overlapping Center Has Vanished: In the mid-20th century, the ideological distributions of the two parties overlapped significantly. There were liberal Republicans, particularly from the Northeast, and conservative Democrats, primarily from the South. These “cross-pressured” members were crucial brokers of compromise.

- The Great Sorting: Starting in the 1970s and accelerating after the 1994 Republican Revolution, the parties began to sort themselves ideologically. Conservative Democrats either retired, lost primaries, or became Republicans, while liberal Republicans all but disappeared.

- The Pull to the Poles: Today, the Democratic and Republican clusters in Congress are further apart than at any time since the end of Reconstruction. There is virtually no overlap. The most conservative Democrat is now well to the left of the most liberal Republican.

1.2 The Decline of Bipartisan Cooperation

The ideological separation is reflected in the collapse of bipartisan collaboration.

- Fewer Bipartisan Votes: The percentage of bills passed with significant support from both parties has plummeted. Legislation is now typically passed on a party-line vote, with the majority party using its procedural power to muscle through its agenda.

- The Disappearing “Friendly Amendment”: It was once common practice for a member to offer an amendment to a colleague’s bill to improve it, even across party lines. Today, amendments are often used as “poison pills” or political weapons to force the other party into an uncomfortable vote.

- Co-Sponsorship Networks: Analysis of bill co-sponsorship shows that members of opposite parties are far less likely to work together on legislation than they were just 30 years ago.

1.3 Rhetoric and Affective Polarization

The division is not just about votes; it’s about feelings. Affective polarization—the tendency for people to dislike and distrust those from the other party—is at a historic high inside the Capitol.

- Dehumanizing Language: Political rhetoric has shifted from disagreeing with an opponent’s ideas to questioning their motives, patriotism, and character.

- The Social Schism: Members of Congress from opposing parties report having few, if any, social relationships with one another. They no longer carpool together, their families do not socialize, and they often don’t even live in the same Washington, D.C., neighborhoods. This loss of informal connection destroys the social capital necessary for trust and compromise.

Section 2: The Root Causes – A Perfect Storm of Polarizing Forces

The current state of Congress is not an accident. It is the result of a confluence of long-term trends and deliberate strategic choices.

2.1 The Realignment of the South and the End of the Conservative Democrat

The single most significant political event of the last 60 years was the realignment of the American South. The Democratic Party’s embrace of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, began a decades-long process of white conservative voters in the South leaving the Democratic Party for the GOP. This slowly purged the Democratic Party of its most conservative members and turned the South from a Democratic stronghold into a Republican one. This “sorting” created two more ideologically coherent, and therefore more distinct, parties.

2.2 Geographic Self-Sorting and the Rise of the “Safe Seat”

Americans are increasingly choosing to live near people who share their political views. This phenomenon, detailed in Bill Bishop’s book The Big Sort, has profound electoral consequences.

- Homogeneous Districts: As liberals cluster in dense urban areas and conservatives dominate rural and exurban areas, congressional districts become politically homogeneous.

- The Primary Election Problem: In a safely Republican or Democratic district, the only competitive election is the primary. Primary electorates are typically smaller, older, and more ideologically extreme than the general electorate. To win a primary, a candidate must appeal to the party base, pushing them away from the center and making compromise with the other party a dangerous liability.

- Gerrymandering: While not the primary driver of polarization, partisan gerrymandering exacerbates it. By drawing districts to be “safe” for one party, state legislators reduce the number of competitive districts, further insulating incumbents from general election pressures and making them accountable only to their primary voters.

2.3 The Media Revolution: From Shared Facts to Fragmented Realities

The media landscape of the mid-20th century—dominated by three major broadcast networks—created a common set of facts for the American public. The rise of cable news and, later, the internet, shattered this consensus.

- The Rise of Partisan Media: The advent of 24-hour cable news created a market for opinion-driven, partisan programming. Outlets like Fox News and MSNBC did not just report the news; they framed it through a distinct ideological lens, creating separate information ecosystems for conservatives and liberals.

- The Social Media Amplifier: Social media platforms prioritize engagement, and outrage and conflict are highly engaging. Algorithms create “filter bubbles” that reinforce existing beliefs and present the other side as not just wrong, but ridiculous or malicious. For members of Congress, social media provides a direct channel to rally their base, often through performative outrage, bypassing traditional journalistic filters and further deepening animosity.

2.4 The Changing Nature of Money in Politics

The role of money in political campaigns has fundamentally changed how members of Congress behave.

- The Rise of Outside Groups: The Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision and related rulings unleashed a flood of money from Super PACs and dark money groups. These groups often have purer ideological agendas than the parties themselves.

- The Fear of a Primary Challenge: A member of Congress who is perceived as too moderate can quickly find themselves the target of a well-funded primary challenge from a more extreme candidate, backed by these outside groups. This creates a constant incentive to maintain ideological purity.

2.5 The Erosion of Institutional Norms

Congress has long relied on unwritten norms and traditions to function effectively, even in times of partisan strife. Many of these norms have eroded.

- The “Regular Order” Breakdown: The traditional legislative process—committee hearings, markups, floor debate—has been short-circuited. Major legislation is increasingly drafted by leadership in secret and brought to the floor under closed rules, limiting debate and amendment.

- The Weaponization of the Filibuster: While the talking filibuster was once a rare tool, the 60-vote threshold to overcome a filibuster in the Senate is now used routinely, requiring a supermajority for almost all significant legislation. This has normalized gridlock.

- The Hollowing of Committees: Committees were once where the substantive work of Congress was done and where cross-party relationships were built. Their power has been centralized in party leadership, diminishing their role as incubators of compromise.

Section 3: The Consequences of a Divided Congress

The deepening partisan divide is not an abstract political science concept. It has tangible, often negative, consequences for American governance and society.

3.1 Legislative Gridlock and Governance by Crisis

The most direct consequence is an inability to pass legislation on a wide range of issues. Complex, long-term challenges like immigration reform, entitlement solvency, and climate change become politically impossible to address. This leads to:

- Government Shutdowns: When Congress cannot pass routine spending bills, the government shuts down, disrupting services and harming the economy.

- Governing by Brinksmanship: Routine acts, like raising the debt ceiling to pay for debts already incurred, become hostage-taking opportunities, creating periodic economic uncertainty.

3.2 The Erosion of Public Trust

When the public sees a Congress perpetually mired in partisan fighting and unable to solve problems, trust in the institution plummets. Congressional approval ratings have been in the teens or single digits for years. This erosion of faith in a core democratic institution is a long-term threat to the health of the republic.

3.3 The Nationalization of Politics and the Neglect of Localism

In a deeply polarized environment, every election becomes a nationalized referendum on the president and the national party brand. This means:

- Local Issues Take a Back Seat: A representative’s ability to deliver for their specific district (through earmarks, constituent services, and localized legislation) becomes less important than their national partisan identity.

- The Decline of the “Work Horse”: The incentive structure rewards the “show horse”—the member who excels on cable news and social media—over the “work horse” who toils in committees to craft nuanced policy.

3.4 The Impact on the Judiciary and Executive Branch

Congressional dysfunction has ripple effects across the entire federal government.

- Judicial Confirmations Become War: The process of confirming federal judges, especially Supreme Court justices, has become a bare-knuckle political fight, viewed as a way to achieve policy goals that are unattainable through the legislative process.

- Abdication of Power: An ineffective Congress often cedes power to the executive branch. Unable to pass detailed laws, Congress writes broad statutes, delegating immense rule-making authority to federal agencies. It also fails to robustly exercise its oversight power when the president is from its own party.

Read more: 10 Billion Reasons: Will the 2026 Midterms Break Records in Ad-Spending & Influence?

Section 4: Potential Pathways Forward: Is There a Cure for the Divide?

Reversing decades of polarization is a monumental task with no easy solutions. However, several reforms and shifts could begin to mend the fractures.

4.1 Electoral Reforms

Changing how we elect our representatives could alter the incentives that drive polarization.

- Non-Partisan Redistricting: Taking the power to draw congressional districts away from state legislatures and giving it to independent, non-partisan commissions would create more competitive districts, forcing candidates to appeal to a broader electorate.

- Ranked-Choice Voting (RCV): RCV allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference. It discourages negative campaigning, as candidates need to be the second choice of their opponents’ supporters. This system can reward more moderate, coalition-building candidates.

- Open and Top-Two Primaries: These primary systems, used in states like California and Washington, allow all voters to participate in a single primary, with the top two vote-getters advancing to the general election, regardless of party. This can reduce the power of the partisan base.

4.2 Congressional Rule Reforms

Congress could reform its own procedures to encourage collaboration.

- Restoring “Regular Order”: Empowering committees, allowing for more open amendment processes, and reviving the practice of conference committees would create more opportunities for bipartisan negotiation.

- Reforming the Filibuster: Reforms, such as requiring a talking filibuster or lowering the vote threshold for certain types of legislation, could reduce gridlock without eliminating the minority’s voice entirely.

- Bipartisan Caucuses and Retreats: Encouraging and funding formal and informal gatherings where members from both parties can interact socially and discuss policy in a non-adversarial setting can help rebuild relationships.

4.3 A Cultural Shift

Ultimately, technical fixes will only go so far without a shift in political culture.

- Civic Education: A renewed emphasis on civics that teaches the value of compromise, civil disagreement, and the structures of democratic government is essential for the long term.

- Responsible Media Consumption: The public has a role to play in seeking out diverse, credible news sources and breaking out of their information silos.

- Demanding More from Leaders: Voters must reward representatives who demonstrate a willingness to work across the aisle and solve problems, rather than those who specialize in partisan theatrics.

Conclusion: The Republic’s Greatest Test

The deepening partisan divide in Congress is more than a political problem; it is a systemic challenge to the American experiment in self-governance. The Framers designed a system of separated powers that required compromise to function. They feared the “violence of faction,” and the current era shows their fears were well-founded.

The path back from the brink will be long and arduous. It requires a clear-eyed understanding of the structural forces at play, a willingness to reform our institutions, and a collective commitment from politicians, the media, and the public to rebuild a culture of democratic pragmatism. The motto of the United States, E Pluribus Unum—”Out of Many, One”—has never been a statement of fact, but an aspiration. In an age of deep division, recommitting to that aspiration is the most urgent task facing the nation. The future of a functional, representative government depends on it.

Read more: How Is Social Media Shaping American Political Campaigns?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is today’s partisan divide really worse than in the past? What about the Civil War era?

While the Civil War era was clearly the most violent and fundamental division in American history, it was primarily a regional and moral conflict over slavery, not purely a partisan one within a functioning Congress. The current partisan divide is unique in its comprehensive nature—it is ideological, geographic, cultural, and affective (driven by emotion and identity). In terms of the sheer ideological distance between the two parties within Congress and the level of social animosity, political scientists like Poole and Rosenthal have shown that we are in a period of historically high polarization, rivaling or exceeding the late 19th century Gilded Age.

Q2: Isn’t some level of partisanship healthy for democracy?

Yes, to a point. Healthy partisanship involves loyal opposition, where parties present distinct policy visions, debate them vigorously, and then accept the outcomes of elections. It becomes unhealthy when it morphs into hyper-partisanship or affective polarization, where the goal shifts from governing to defeating the other side at all costs, and where the other party is viewed not as a legitimate opponent but as an enemy. This is the state we are in now, and it undermines the trust and cooperation necessary for a democracy to thrive.

Q3: Who is more to blame for the divide—Democrats or Republicans?

Assigning unilateral blame is a symptom of the very problem this article describes. The drivers of polarization are systemic and long-term. Both parties have moved further apart ideologically. Both parties have engaged in gerrymandering when given the chance. Both have partisan media ecosystems that support them. And members of both parties face similar incentives from primary voters and donors that pull them away from the center. Focusing on which party is “more” at fault often prevents a clear-eyed analysis of the structural issues that affect the entire system.

Q4: Can’t the President just force Congress to work together?

The President’s power over Congress is limited. While the President can set an agenda and use the “bully pulpit” to pressure lawmakers, the Constitution grants all legislative power to Congress. A president who tries to strong-arm an independent and polarized branch often provokes a backlash, further entrenching opposition. Ultimately, the culture and rules of Congress must be reformed from within; the President can be a catalyst, but not the sole architect, of such change.

Q5: What is the single most impactful reform we could make to reduce polarization?

Most political scientists and governance experts point to electoral reform as the highest-impact area. Changing the incentives that drive politicians’ behavior is key. A combination of non-partisan redistricting to create more competitive districts and the adoption of ranked-choice voting to encourage broader appeals would fundamentally alter the political calculus for candidates, making compromise less dangerous and more rewarding. This would not end polarization overnight, but it would begin to re-center the political system.

Q6: As an individual voter, what can I do to help reduce political polarization?

- Vote in Primaries: This is where you have the most influence. Support candidates who demonstrate a willingness to work across the aisle and who focus on practical problem-solving.

- Engage Constructively: In your own conversations, especially on social media, focus on issues rather than personalities or motives. Seek to understand the underlying values of those you disagree with.

- Diversify Your Information Diet: Make a conscious effort to read news from sources with different editorial perspectives to break out of your filter bubble.

- Support Cross-Partisan Organizations: Consider supporting non-profit organizations dedicated to promoting civil discourse and bipartisan policy solutions.

- Hold Your Representative Accountable: Write to your member of Congress and express your support for bipartisan cooperation and institutional reforms.